If you have a book you’d like considered for a review in Light—one that includes a large helping of light verse and was published within the previous 12 months, or will be published in the next eight—please send a copy to:

Barbara Egel

PO Box 408250

Chicago, IL 60640-0005

(Pre-print-run electronic copies may be sent to lightpoetryreviews@gmail.com)

Light on Their Feet

by Barbara Egel

(Reviews of books by Brian Allgar, Ned Balbo, A.M. Juster, Daniel Klawitter, and the Powow River Poets)

The Misuse of Scripture, by Daniel Klawitter. 2020.

It’s pretty obvious that Daniel Klawitter, a religious brother in the order of St. Luke, does not fit the clerical stereotype. His book fails spectacularly (and I mean that in a good way) at modesty, abstemiousness, overt piety, and the kind of performative humility that masks intellectual laziness or lack of imagination. The poems here—each inspired by a specific Bible verse—use humor as a form of agape, painting the Bible’s authors as humans with a sense of the absurd and with faith that God can take a joke. Certainly, the poems don’t always—or often—go in the direction their epigraphical scriptures might suggest. “Red Stuff” harks back to Genesis: “And Esau said to Jacob, Feed me, I pray thee, with that same red pottage; for I am faint.” What follows is a list of red things in rhymed couplets, including a “socialist padre” and “that sweater for Christmas with its horrid design.” Klawitter’s irreverence surfaces midway through the poem when he rhymes “precious red rubies” with “some people’s boobies.” That womanizer Jacob might have been a fan, but it’s certainly not what the reader expects. Similarly, the verse from Mark, chapter 14 about taking up serpents and drinking poison results in “The Small-Town Drunk Goes Church Shopping,” which ends with the lines,

But them Pentecostals take their religion

The way I often make my whisky:

Volatile, risky, and hard.

The rhyme technique Klawitter uses in those last two lines—an end-rhyme matching a word midway through an adjacent line—appears throughout the book and is surprisingly not disruptive. The reading ear places the words easily while the eye plunges forward.

Part of the pleasure of this book is realizing how bizarre some Bible quotes are when taken out of context. Klawitter does treat some of the more famous verses, as in “The Knowledge of Good and Evil,” but often his attention is captured by verses that, in the Bible, feel like exposition on the way to a revelatory plot point, or that are simply not in the stories that permeate our culture. For example, the verse from Ezekiel about the prostitute, Oholibah, lusting after men “whose genitals were like those of donkeys” isn’t in the Sunday School curriculum, but it yields a wonderful poem, “Yes, But Does He Write You Poetry?” whose speaker feels a bit insecure about his endowments.

The more serious poems in the book are striking, especially in contrast to their lighter mates. Inspired by Proverbs, the sonnet “In Sickness and in Health” depicts its speaker’s longing to take away a loved one’s pain.

But love, though under duress, is never destitute.

Even in the face of hell it hopes for paradise.

Even in purgatory it yearns for heaven:

Even in this hospital, that burns like Armageddon.

Theologically, The Misuse of Scripture lies somewhere between the Talmud scholars and Chesterton’s Father Brown. Poetically, it is a rewarding book: engaging light verse that makes you think about what the Bible’s many authors might have really meant.

An Answer from the Past: being the story of Rasselas and Figaro, by Brian Allgar. Kelsay Books, 2020.

As with his previous book, The Ayterzedd, Light contributor Allgar has hit that sweet spot between “Baby Shark” and Downton Abbey: writing that will captivate children without leaving their grown-ups in need of silence and a stiff drink. Unlike the previous book, which was an abecedarian bestiary (try saying that ten times fast), An Answer from the Past is a narrative in rhymed couplets. It’s the story of Prince Figaro and his eventual lifelong friend, an elephant named Rasselas, who has lost his memory and needs to find his way home.

Figaro is “a prince of royal blood,” son of a well-meaning king whose love of opera gets in the way of his really hearing what Figaro tells him. Rasselas appears, asking for help finding his way back home. Before they depart, they are outfitted for the trip in a rhyming list that is absolutely delicious: “A bag of apples, green and red / A jar of honey, loaves of bread, / Some chocolate, a dozen eggs, / a tent, a hammer, wooden pegs”—you get the idea. There is something immensely pleasing about a long list of objects that are rhymed as carefully as they are packed.

As the two travel, they meet a crocodile; a Cockney hippo who gives excellent, if unheeded, advice; the Florence Foster Jenkins of peacocks; and an aristocratic lion that likes to play with its food:

He heard a large, contented purr,

And saw a coat of ragged fur,

A tawny eye, a grip of iron:

“Pleased to meet you,” said the lion,

“Don’t get up on my behalf.”

As the adventure progresses, elephant and prince form a bond of friendship and trust. Of course, Rasselas gets his memory back—in a flashback reminiscent of Bambi’s mother (so maybe paraphrase that part with more sensitive little souls)—and ultimately returns to his people. There are hints here and there at a larger point being made (Figaro’s kingdom is, after all, called Paraphrasia), but I will leave that discovery for you.

This is a gentle book, and even as the plot is familiar, the language and feeling are unpredictable enough to absorb all readers. The only regrettable aspect of this book is that it’s not fully illustrated. An Answer from the Past deserves visual representation of all the color and character the words conjure.

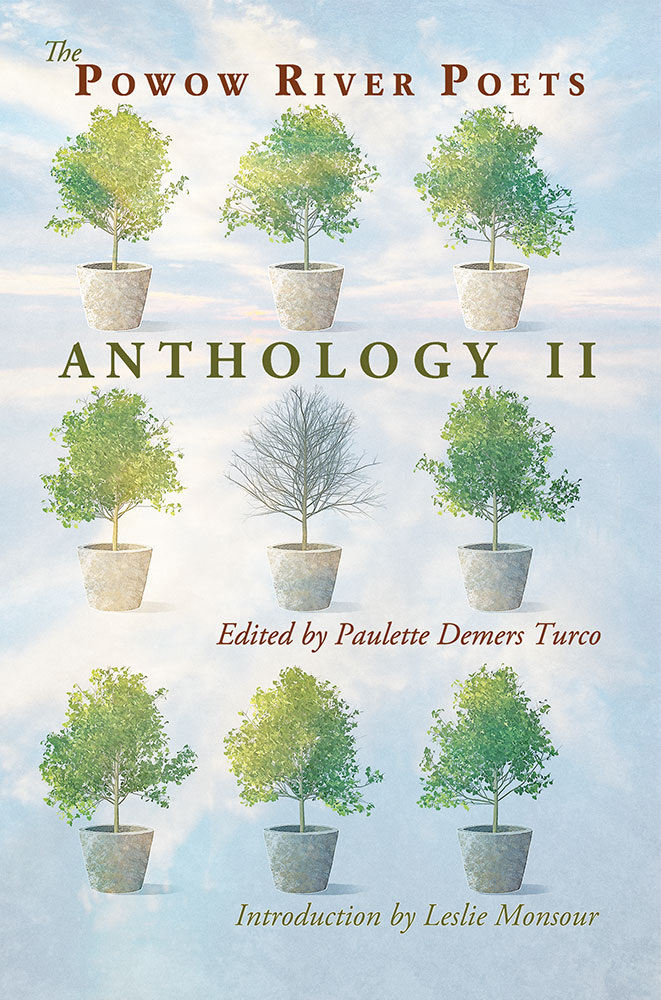

The Powow River Poets Anthology II, edited by Paulette Demers Turco. Able Muse Press, 2020.

The obvious metaphor for the Powow River Poets would be a small, privately held company dedicated to the production of high-quality, one-of-a-kind goods. The group, including award-winning poets, many of whom have appeared in Light, has been humming along for thirty years or so, arousing both awe and envy in poets who wish they lived closer to Newburyport, MA. As Leslie Monsour writes in her affectionate introduction, the soul and spirit of the group is Rhina P. Espaillat. One wonders at a Dominican political refugee tempered by a life spent in New York City—what kind of alchemical reaction happened when she first breathed the astringent air of small-town coastal New England? Whatever it was, it should be bottled and sold in small, expensive doses. The miracle of the Powow poets is that while some have moved away and others joined, the center has held, in both the group’s integrity and its aesthetic. The first Powow Anthology, published in 2006, includes many of the same names as this one. The quality and feel of the poems remains as well, though the group hasn’t stagnated, as exemplified by Wendy Canella’s powerful free-verse poem, “The Word Slut.” Monsour notes that “what these poets require of themselves are poems that are made to be understood.” Whatever you do, don’t mistake that clarity for simplicity or lack of depth. There is a lot here that invites repeated, sustained engagement.

Several Light favorites are Powow members represented in this anthology, including Espaillat herself, Meredith Bergmann, Michael Cantor, Barbara Lydecker Crane, Robert Crawford, Midge Goldberg, A.M. Juster, Jean L. Kreiling, Alfred Nicol, and Kyle Potvin, and some of the poems appeared here first.

The fact that the Powows take seriously the structural rigor and marrying of form and theme crucial to light verse is apparent throughout the book. Anton Yakovlev’s frightening poem, “The Informant,” illustrates the banality of evil using an almost Dr. Seuss-like rhythm to recount a disappearance behind the iron curtain. The effect is of a horrifying event so commonplace as to be singsong. Kyle Potvin’s “To My Children Reading My Poetry After I’m Gone” reads like a less ruthless Marilyn Hacker poem. Potvin contemplates the contrast between the mother they know and the persona in her poems, in a mix of elevated and daily language that both lightens the poem and embodies the contrast she explicates.

Other standouts on the border of light and serious include Andrew Szylvasy’s “Faculty Welcome,” which follows a young woman from her hometown where “She doesn’t get ‘the sports’ and hates hot fashion; / in one ear Gronk, the other a Kardashian,” and compares her ways of faking erudition with colleagues and faking rapport with family:

She’s smirked through many a male peer’s lectures, bluffed

her love of Mondrian, and gently smiled

at Dad, who smoothly shepherds guests to his loved

Kinkade he bought online. . . .

We are shown, rather than told, what her feelings are and how she’s navigating, which leaves us feeling smart and sympathetic.

Of course there are purely light poems here as well. A.M. Juster’s “Houseguests” imagines a literary party in which writers from several eras share the same hors d’oeuvres plate. It includes not only Ginsburg and Larkin finding a way to bond but also has Emily Dickinson gleefully giving in to Dylan Thomas’s advances (at least, I assume that’s the “Dylan” he means—take your pick, I guess) and Rimbaud idly surfing the Net. The cleaning bills will be exorbitant. Rhina P. Espaillat has a dialogue with God in which she all but offers him chicken soup and a lie-down, Robert Crawford gets heated up while “Kitchen Remodeling,” and Alfred Nicol delivers simple, natural, no-sugar-added sweetness in “One Day.” In all, there is considerable light verse ability here, and it leavens the rest of the collection without feeling disruptive. Anne Mulvey’s “Teen Angels: High Hopes Circa 1960” isn’t really light, but the final line is a shot of wry and a wonderful wrap-up to the sonnet.

There’s a lot more to discover in this book, including Toni Treadway’s concentrated, atmospheric poems, David Davis’s string of gorgeous sonnets, and M. Frost Delaney wondering “What Joseph Might Have Said.”

The anthology makes clear that the Powows are not all formalists, not all light-versers, but their poems are all “made to be understood,” and I hope that standard continues for at least another thirty years.

Wonder and Wrath, by A. M. Juster. Paul Dry Books, 2020.

Juster’s book, which includes new and previously collected poems, was written and assembled before the COVID pandemic, but it seems to have anticipated the abrasion of the nerves we all suffer from as we wait to reconnect with normal life. As expected from the multiple-Nemerov Sonnet Award winner, the craft in these poems is masterful, running to villanelles, a chilling pantoum (“Falling for the Witch”), free verse, and, of course, sonnets. This is Juster’s first non-translation, non-parody, not-entirely-light-verse book in quite a while, and it is worth the wait.

A lot of this book is very serious, but the humor it does include is appropriately dry and dark for our present moment. Or perhaps it’s less about humor and more about situational ridiculousness captured by an unflinching eye and exacting poetic impulse, as in “I Sit Half-Naked,” in which the speaker, dressed in a breeze-catching medical gown, dissects the difference between the English word “depression,” which carries the promise of a rise out of the depths, and its Spanish translation, “dolor,” which is only about the depths. The image of a person waiting endlessly for the doctor as their dignity seeps away, coupled with Juster’s linguistic and sympathetic insight, is, if not laugh-inducing, certainly a special episode in the human comedy.

Similarly, “A Midsummer Night’s Hangover” considers the disservice done to high school theater nerds who, having achieved the magic of Shakespeare’s fantasy—and its after-party—find themselves the next day thoroughly let down as reality reasserts itself. Nobody warned them how fraught it is to strike a set:

Dyspeptic Puck yanks birches from their stands;

mechanicals unhook the fruitless moon.

Demetrius considers Helena

in jeans, and mopes as he recalls her strands

of spotlit hair. Fair Hermia still beams—

and reaches for Lysander in her dreams.

“Rounding Up the Mimes” is a poem that calls John Whitworth to mind, specifically poems like “The Examiners,” in which a pointed argument is being made among tropes and images so wildly weird that the end result is unease. There’s also a hint of Shirley Jackson in the poem’s exploration of wholesome community hate. Its rhetorical subject is fear of difference without the facts to back up any real suspicion. The mimes are subjected to tortures tailor-made for their kind. How does a reader respond to “kids trapped another inside a box / of glass for days—and told him to ‘pretend / to eat a sandwich’”?

A final section at the end collects more of what Juster has been doing lately: some translations, including a selection of Aldhelm’s riddles, and translations “from the English” of Billy Collins and Bob Dylan, with which you can gleefully tease the fans of those writers perhaps without them even knowing.

Wonder and Wrath is a title for our moment, alternately articulating our anger, hurt, and malaise and lifting us out of it with humor that doesn’t deny reality.

The Cylburn Touch-Me-Nots, by Ned Balbo. Criterion Books, 2019.

Winner of the New Criterion Poetry Prize, Balbo’s latest is a different kind of appropriate-for-a-pandemic. The elegiac, recollective quality of much of this book fits our moment: we long less for the quaint corner diner that closed decades ago and more for any kind of contact, however charmless the setting. Several poems musing on the speaker’s complicated family connections are scattered throughout the book, giving readers a half-formed picture of the tangle of relationships that mirrors the sketchy understanding of the children involved.

A few poems are lighter. The sonnet “Late to Yoga” has a pull-over-and-think-about-it level of irony, describing a woman who tailgates, texts while driving, and otherwise puts health and safety at risk in order to get to a yoga class on time—which she’s taking presumably to attain wellness and inner peace. This and “Meaningless Sex” and “Poetry and Sex” are the book’s lightest pieces. All the poems are executed with skill, both in free verse and received forms. About halfway through the book, it feels as if Balbo has tapped into some kind of ur-memory. You haven’t had his specific experiences of love, loss or confusion, but the ones you have had felt the same way. You smile and wince, happy to have lived through them.

The Cylburn Touch-Me-Nots (another of Balbo’s I-dare-you-to-remember-that book titles) is infused with the kind of connection we took for granted a year or so ago, and reading it with that connection lost is all the more poignant. This is a lovely, affecting book.

Also Over the Transom

In or Out of Season, by Jane Blanchard. Kelsay Books, 2020.

Magic Words: Lively Poems for Clever Kids, by Phil Huffy. 2020.

Voice Message, by Katherine Barrett Swett. Autumn House Press, 2020.