by Barbara Loots

When You Care Enough to Send the Very Best. By the time I stepped into my cubicle at Hallmark as a fledgling greeting card writer, the slogan was engraved in the minds of American consumers. Back in the 1930s, a Chicago radio personality named Tony Wons had brought friendly companionship and inspiration to housewives from coast to coast. Hallmark sponsored Tony’s Scrapbook, a broadcast in which Wons intoned Hallmark “poems” on the air. Afterwards, he told the ladies to turn the card over and look for the name “Hallmark.” What self-respecting greeting card buyer would risk sending her mother-in-law anything else? A decade or so later, the famous slogan was created, along with the familiar crown logo.

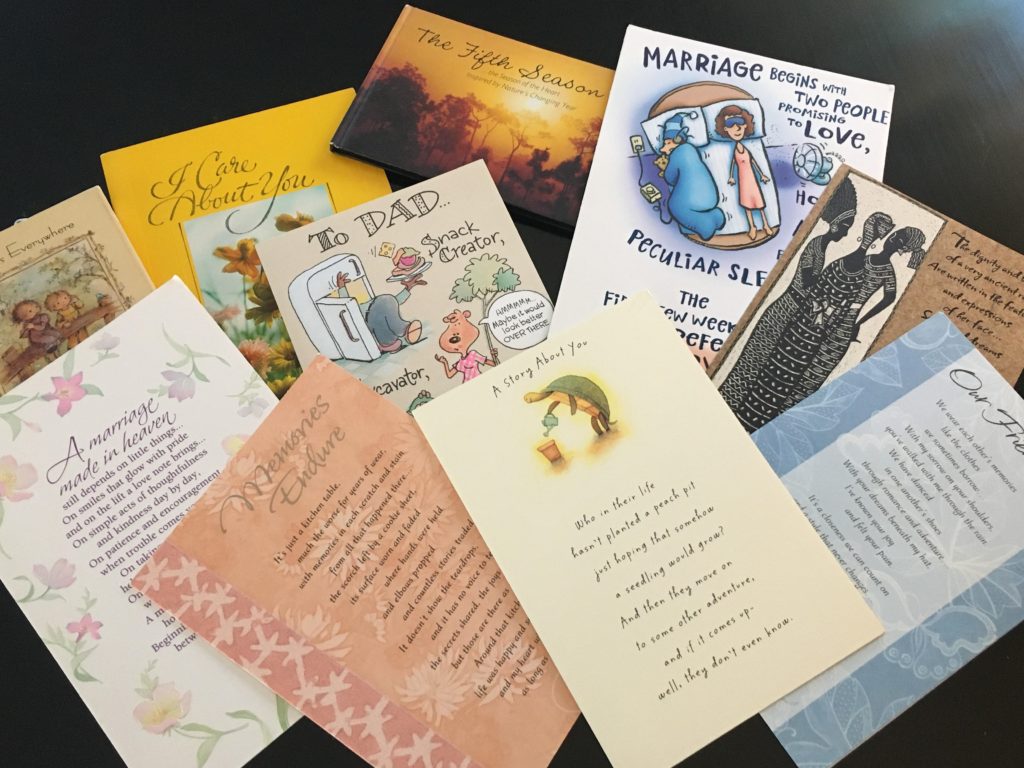

The cards were, in fact, the very best. The paper stock was heavier and whiter than that of other greeting cards. The colors were brighter, as Hallmark founder Joyce C. Hall insisted on an expensive five-color separation process. Proprietary typography and calligraphy, with title lettering hand-drawn for nearly every individual design, distinguished a Hallmark from any other greeting card on the market. Mr. Hall expected a high standard of skill, originality, and taste from his stable of artists. A select group, they employed techniques from watercolor to embroidery to wood collage.

That was Hallmark when I got there in 1967.

Landing the Job

My college professor took a dim view of my writing skills. He was a would-be novelist, with a record of publications mostly in male-oriented magazines. Perhaps he was not such a good fit with the genteel constituency of the women’s liberal arts college in the Deep South where our paths crossed. But in my final year, I needed the credits. I was disappointed in his dismal evaluations of my proposals and articles, so I sat for a consultation.

A little exasperated, he asked, “Just what is it you want to write, Miss Kunz?”

“Poetry,” I said.

“You’ll starve!” he said.

Harsh as it sounded, he had a point. How did poets earn a living? I was vaguely aware that some of them occupied space in academia. But I didn’t want to teach. I had tried out the advertising world as a summertime go-fer at an agency back home. Writers made a living in advertising, didn’t they? What else? According to this professor, my prospects in freelance journalism were slim to none.

Meanwhile, far away in Kansas City—my birthplace, as it happens—a relative came up with a bright idea: Why don’t you apply to Hallmark? You like to write that kind of thing. By “that kind of thing” she meant sentimental rhymed verse for all occasions, for which I had long been the family scribe. Why not? I sent for the application.

The Hallmark writer application consisted of a series of assignments pertinent to, naturally, greeting cards. In many subsequent years, it remained substantially the same for every writer who wanted to pass muster for the job. For example:

Write a four-line rhymed verse to cheer up someone (man or woman) who is ill.

Read the next four examples, and choose the one that is most appropriate for a grandmother who lives at a distance from her grandchildren on Mother’s Day.

Which of the following sentiments is most restrictive as to sendability?

Sendability. A word that was soon to become the mantra of my existence.

I sent off the completed application with low expectations.

Some weeks before graduation, a bit worried that homelessness loomed in my future, I received a letter from Hallmark. They wanted me to come to Kansas City, fully halfway across the country, for an in-person interview.

Trust me. In 1967, few “girls” got invited to cross the country at company expense for a job interview. Unless you were male, you usually went straight from college to public school teaching, nursing, a secretarial job, or the marital bed. I flew to Kansas City.

I wore white gloves to the interview. I should say interviews, because I spoke on that one day with many people. Editors, managers, supervisors, personnel representatives, and finally, the vice-president of Editorial. He was, to say the least, intimidating. Later I found out that being confrontational (on the brink of rude) was his shtick. He laid it on thick for a naïve, eager, and very prim young poet. I was a literary ignoramus in the presence of this man, who was (I later learned) a well-known critic who contributed commentary to literary publications like The Atlantic Monthly. I bumbled through his interrogation, in the end feeling inarticulate and hopeless.

That very day, I was offered a job as a Hallmark writer at a salary that sounded like a fortune.

Learning the Lore

Just so you know, I also got offered a job at that advertising agency close to home. And thanks to the intervention of a gracious professor at my college, I had the opportunity for a graduate fellowship at a fine university where I might have met, early on, some of the poets and teachers who later became influential in my life. But…

I picked Hallmark Cards. How tough could that be?

Very. As it turns out.

We writers worked at manual typewriters in a glass-enclosed space known as the Writers’ Room. As you’d expect, we were assigned to write greeting cards for particular “sending situations.” The instructions our editors gave us were very specific: occasion, number of lines, tone, theme, and other restrictions. Instructions included details such as I or No I; Avoid superlatives; Gratitude theme. Often certain rhyme schemes were to be avoided. In fact, there was a general disdain for the commonplace way/day/you/too combination of word and sound—a rather heavy burden in a business where the most powerful of all endings and intentions is the word YOU. Cultural shifts had already eliminated “gay” from our rhyming opportunities, let alone our cheery seasonal wishes.

Within a short time, I found out that all my poetical persuasions were a dreadful handicap. My attempts to bring “fresh imagery” or “more realistic life situations” into the stodgy, unsurprising conventions of greeting cards were met one hundred percent with NO. Occasionally, from the stringent “review committee” of editorial managers, I received an encouraging “Have sim”—meaning that something similar was already in the files. At least I was on the right track.

The range of styles and ideas was extremely narrow. And yet, day after day, expectations were high that I, and the five or six other writers, would succeed in saying Happy Birthday in four or eight lines of rhymed verse never before thought of. Rejection piled on rejection. My drawer filled up with 3×5 cards, each with a scribbled NO. My spirit failed. I gazed out the window a lot.

My Hallmark handlers, however, held out with extreme patience. Eventually, I began to get with the program. I suppressed my desire to advance the humble greeting card to a higher level of literary and emotional integrity. I mastered the nuance of saying nothing committal in a sweet-sounding package of verse. I wrote tiny new spins on Happy Birthday. I put words in the mouth of Snoopy.

Occasionally, I managed to inject a bit of poetic craft, and it worked still within the genre of the me-to-you message:

There aren’t enough words

to tell you I love you,

Not enough ways

to show you I care,

Not enough laughter

and good times to wish you,

Not enough wonderful moments

to share…

A million bright mornings

would not be too many,

Long evenings forever

would still be too few,

For I need you and love you

so much that it seems

There aren’t enough days

in a lifetime with you!

That verse became a perennial bestseller.

By the time I wrote the following verse, I had met and married a fellow “Hallmarker” who became my romantic inspiration for thirty-eight years. Our vacations at the Atlantic shore—a long drive, but worth it—prompted the imagery of another best-selling sentiment. If you restructure the line breaks (devised by the lettering artist to fit the space), you’ll discover a sonnet:

Two Upon the Shore of Life

Like pebbles

side by side upon the sand,

together we’ve endured

the push and pull

of time’s relentless waves.

Still hand in hand, we stand,

where all is movable, unmoved.

Unending love has made us one

against the toss and tow

of wind and sea.

Now smoothed and polished

by the rain and sun,

our separate lives

are shaped in unity.

You are still you,

in ways that have not changed

since we were brought together long ago.

I am still I, and time that rearranged our features

cannot dim the heart’s deep glow.

We shine together

in this time and place,

each one the light

upon the other’s face.

Greeting-card writing is an easy target for literary types. But what they call the cliché, I call the familiar. Daily I stepped into the minds of other people, trying to capture what they might want to say, or couldn’t even imagine saying, in the most delicate relationships and emotionally powerful events of their lives. It was poetry to the people who bought greeting cards. I knew the difference, and I was comfortable using the resources of language for whatever purpose I meant to serve. At the same time, I learned to handle rejection with sangfroid, because rejection was most of my experience.

I was not so self-assured in my private writing life. I still aspired to be a “real” poet, and wondered when someone, somewhere might declare unequivocally that I was one.

Hallmark Gets Better and So Do I

The ’60s and ’70s brought an immense cultural shift to American society, and thus to the “social expression” business of Hallmark as well. Consumers began seeking out greeting cards that more precisely expressed the details of their situations and emotions. New flavors emerged. One in particular was “conversational verse,” which made use of triple meters, colloquial language, and everyday experience to create a sense of authenticity. To achieve this, writers identified certain qualities specific enough to seem real, yet common enough to spark a sense of familiarity in just about anyone. With each such sentiment, we tried to achieve a response something like, “How did they know??” Whether in verse or prose, these messages were meant to hit emotional pay dirt:

Being yourself—

that’s a gift with a purpose!

So please take a moment right now to review

the wonderful, one-of-a-kind kind of person

who’s known as the only, remarkable YOU!

Think of the hope and potential within you,

the kindness you offer, the goodness you share.

Think of the moments when you’ve given comfort

the people who’ve counted on you being there.

Sometimes it’s difficult, painful, or lonely

to stand out uniquely, apart from the crowd.

But those with a beautiful spirit like yours

have the courage it takes

to be different—and proud.

During my seniority as a writer, I persuaded management that scouting for fresh minds for the writing staff was part of my role. A good place to do that, I suggested, was at writing conferences, popular across the country as gathering places for poets, would-be poets, and poetry teachers. By this time, colleges and universities had invented Creative Writing degrees, and liberal arts programs from coast to coast were turning out countless unemployable poets. I believed I might offer a mutually rewarding opportunity to a few of them—but only “the very best.”

Some people in management were skeptical that a Hallmark writer would be well-received in such venues. To the contrary, I found that interest in Hallmark, if only for the allure of an actual job as a writer, was invariably gratifying.

As a considerable benefit, the conferences I chose afforded me personal contact with notable poets like William Stafford, John Frederick Nims, Richard Wilbur, Donald Justice, and many others less well known but highly accomplished and deeply instructive toward my literary ambitions.

To share something of this experience with my Hallmark colleagues, I helped promote an “enrichment” activity: inviting well-known writers to conduct workshops exclusively for Hallmark writers right on the premises. Among our presenters: Alex Haley, Howard Nemerov, Gwendolyn Brooks, Jane Hirshfield, Judd Hirsch, William Stafford, Ted Kooser, Dana Gioia. Our literary guests were pleased to be invited for a pleasant sojourn in a city they would otherwise never have visited, to star in a little literary event. What they discovered, usually to their great surprise, was a klatch of writers adept at their professional craft, and also brilliant at creating poetry and other artful words.

Teaching Myself to Write Poetry

In parallel with my increasing competence as a greeting card writer, I continued to write poems of a literary sort. I began by sending them out to consumer magazines, as well as literary journals. In the ’70s, Ladies’ Home Journal was still publishing verse as “filler” and they accepted two or three of my poems. About forty years later, I would receive an email from a woman who tracked me down via the internet. She would tell me that she had saved a poem of mine clipped from LHJ, displaying it above her desk, or perhaps stuck on her refrigerator, all those years:

Winnowing

How hard it is to winnow the dreams from waking,

To watch the gold illusion drift away

And turning to the delicate grain of morning

Grind it into the plain bread of day.

Other early poems appeared in The Lyric, a literary magazine which styled itself “An Oasis in an Arid Age.” Thanks to a generous endowment, and the commitment of an editorial dynasty, the magazine chugged along through the Free Verse Era publishing sonnets, couplets, and villanelles—paeans to nature, elegies, and other musings on lofty themes, all in crafted lines that rhymed. The Lyric’s editors and contributors were, and are, my First Family of poetry peers.

However, following the persuasions of influential mid-twentieth century poet-critics, most literary magazine editors exclusively favored free verse and experimental forms. Poetry employing rhyme and meter and fixed forms disappeared from literary fashion and the literary press. It was considered reactionary. Or fascist!

My rejections from numerous “little magazines” piled up. Perhaps it was time for me to change course and go with the (unmetrical) flow. So I vowed, for one year, to write nothing in meter. No blank verse, no sonnets, no Emily Dickinson-style stanzas. Not even a thought of a villanelle or a triolet. Formless only. Free verse only. No fascist formality for me!

More of my poems began to get published.

This brings up a reason why I wanted to write poetry in the first place, and write it well: I wanted to be good enough to get into the conversation with living poets I liked. I wanted to join the party. My library accumulated poetry anthologies and I envisioned someday being in one. There’s a certain frisson seeing one’s name in print over a piece of work you’re proud of, especially among good company.

Perpetually comparing my writing to the work of poets I admired, famous or not, and wondering why the rejections were so frequent, I became darkly self-critical. But how to judge my faults, let alone make improvements, without a classroom, a professorial presence, a teacher? I found my teachers in books.

The best book was given to me personally by its author, the poet John Frederick Nims. We met at one of the writing conferences I spoke of earlier. He gave me a copy of his respected textbook Western Wind: An Introduction to Poetry. Back home, my poetry education advanced substantially as I pored over its pages. At least twice in succeeding years, I called on Professor Nims at his home in Chicago, where he gave me a subsequent edition of Western Wind, and, far more important to me, the delight of his friendship. He never actually critiqued, as far as I know, any of my poems.

Academic Ambition Redux

In 1992, I learned that nearby Baker University was offering a new degree: Master of Liberal Arts. Here was a chance to engage my intellectual side in a wide range of subjects and to finally stick those initials M.A. after my name. Best of all, Hallmark paid tuition for job-related degree programs. In what turned out to be a whirlwind three years, I studied Russian history, the Reformation, the Korean War, the Psychology of Humor, The Brain, The American Novel, The Music of Chopin, and a few other subjects adding up to my shiny new degree. I loved being in school again.

With my new credential fresh in hand, I accepted an offer from Baker to teach evening classes as an adjunct in that same degree program. Etymology. Robert Frost. Contemporary American Poetry. As it turned out, teaching was not as enjoyable as learning. After a few semesters trying out the role, I said goodbye to Baker, with gratitude.

Can Poetry Matter?

About the time I collected my degree, I came across an article in The Atlantic Monthly written by poet and business executive Dana Gioia. It was titled “Can Poetry Matter?” By the time I read the article, it had been circulating in the literary community for at least two years. Gioia attacked the “clubby” subculture of American poetry and its alienation from the intelligent general reader of earlier generations. He offered some suggestions for reviving that interest through more lively public performance and less academic narrowness. Late to the party, I nevertheless wrote him a complimentary letter. A few days after I sent the letter, the phone on my desk rang. The voice said, “Hello, this is Dana Gioia.” As the Brits would say, I was gobsmacked. In time I learned that Dana Gioia was, and is, a world-class networker. I had put myself on his radar.

Soon after that, Gioia and his good friend, Professor Michael Peich at West Chester University, got their heads together over a bottle of wine and decided to establish a new writing conference. This one would be very exclusive, but not in line with existing academic prejudices. Their conference would explore and celebrate Formal and Narrative Poetry, those neglected and even rejected traditions of English verse. Somehow, in split seconds as these things go, they put together the first West Chester Poetry Conference. Being extremely spur-of-the-moment, the conference shaped up as a rather small event. A call went out for scholarly papers, workshop leaders, keynote speakers, panelists, and, of course, participants. I was invited.

I wasn’t by any means a scholar or an academic. However, by then I had published a number of poems in literary magazines. I had earned the MLA degree, and I had taught a few semesters at a university. I had recently read a book titled Natural Classicism, by Frederick Turner, Founders Professor of Arts and Humanities at the University of Texas at Dallas. Among other things, he argued that beauty was rooted in biology. The elements of so-called formal poetry—meter and rhyme and received forms, for example—echo the pulse of the heartbeat, which has everything to do with producing emotional resonance, the sensation of beauty.

That sounded like traditional greeting card verse to me! So I wrote a paper entitled “Public Poetry: The Greeting Card as a Cultural Artifact” and sent it off for consideration as a candidate for an “academic” paper at West Chester. It was accepted.

At that first West Chester conference, in 1995, I met, close-up, poets and scholars practicing and teaching the traditions of English poetry at the highest level. There was teaching, arguing, eating, drinking, and dancing. In the wee hours, alone in my starkly furnished dorm room, I sat nearly stunned with joy. I felt as though I’d arrived in poetry paradise.

My paper attracted a small but attentive audience. Within the year, I pared it down to a print version, and retitled it “Strumming the Neural Lyre” to better reflect its contents: how the tools of formal verse convey emotion in both literary and commercial verse. It was published in Light Quarterly, the print journal that gave rise to this webzine.

I attended the West Chester Conference several times over the next twenty years. Like the Black Mountain poets or the Beats or the Confessional poets of the mid-twentieth century, I now had a label, a school, a movement, as it were, that embraced my poetic convictions: the New Formalists. The craft of poetry, including its traditions of meter and music, clearly mattered to the people gathered at West Chester. And there, my original ambition—to enter as a colleague into the poetry conversation—was fulfilled.

I decided that I was a real poet.