If you have a book you’d like considered for a review in Light—one that includes a large helping of light verse and was published within the previous 12 months, or will be published in the next eight—please send a copy to:

Barbara Egel

PO Box 408250

Chicago, IL 60640-0005

(Pre-print-run electronic copies may be sent to lightpoetryreviews@gmail.com)

Light on Their Feet

by Barbara Egel

(Reviews of books by Michael Cantor, Thomas O. Davenport, David Southward,

William Trowbridge, Zach Weinersmith, and Dede Wilson)

Mrs. H. and Her Tooty-Falooty Ways, by Dede Wilson. Main Street Rag, 2019

When this book turned up in my mailbox, I feared some sort of punching-down character study about an upper-class woman who couldn’t see beyond the end of her own lorgnette. Instead, Dede Wilson, a Light contributor from the print days, offers a complex view of a woman whose glamour hides significant illness and whose husband and daughter take care of themselves in her orbit as best they can.

The poems take place between 1947 and 1949 in a town outside New Orleans and are from the perspective of Mrs. H’s daughter’s best friend, a girl whose own family is comparatively chaotic—and comfortably normal. From the very first poem, “Mrs. H. Insists on a Formal Table,” Wilson demonstrates a theremin-delicate touch in giving us all the details without breaching the limitations of a child’s perspective. The poem’s final couplet,

Mr. H is telling a story. You wonder how he will spin it.

Mrs. H. is laughing her laugh that has no laughter in it.

beautifully illustrates this point of view. By maintaining the young outsider’s perspective, Wilson manages the feat of generating sympathy for an unpleasant person who makes victims as easily as she stirs her perfect martinis (represented in a wonderful concrete poem complete with olive). Indeed, at times, the story told in the poems feels like a child’s humane take on Lillian Hellman or Mary McCarthy: the latent potential for venom never comes to pass. What Wilson does is more interesting and more difficult. She so stirs the reader’s sympathy that one reads these poems with the urgency of reading a novel and feels for all the characters, including the arch, unstable Mrs. H.

Yes, the book achieves some of the lightness suggested by the title. For example, “Every Manner of Things” describes the two girls making fun of Mrs. H’s rigid deportment, and many of the poems demonstrate sophisticated wordplay that will delight Light readers, but once the tone of the book is set, the density of rhyme and the yoyoing line lengths generate the uneasy feeling a child gets when she realizes she’s still laughing even after a situation has turned serious. “Gift for Her 15th Anniversary” buries some rhymes within lines as if to mimic the buried disappointment Mrs. H feels about her too-tasteful/not-big-enough diamond:

The stone that Mr. H. has found, though

not as big as Mrs. H. had dreamed,

will be the most gigantic diamond in this town

Dede Wilson has written a strange and wonderful little book, a snapshot of a time when women wore spectator pumps and wrapped their hair around “rats,” when children yearned for the five-and-dime, and when a trip to the sanitorium was “a visit to her cousin.” There is tremendous craft here and a tumultuous story told so gently and briefly its impact will startle you.

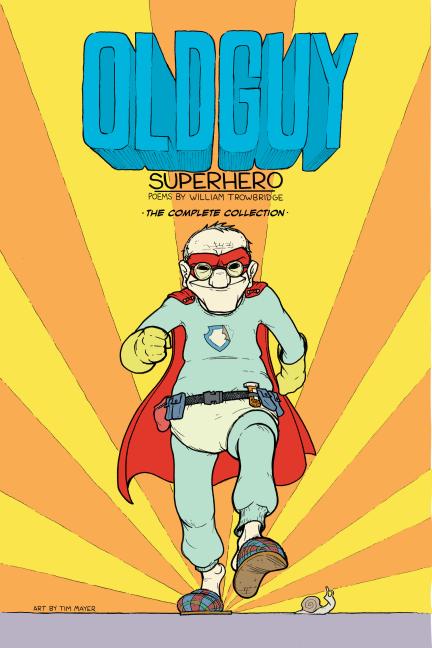

Oldguy: Superhero, by William Trowbridge. Red Hen Press, 2019. Art by Tim Mayer.

William Trowbridge’s book is as easy to underestimate as Dede Wilson’s. The cover shows a cartoon of an old man in carpet slippers and a superhero cape with a pill bottle tucked into his utility belt. I’m ashamed to say I waded tentatively into it expecting at most a pleasant amusement. I got so much more. Oldguy, a sort of existential Mr. Magoo whose best superheroing days are long behind him, still manages to foil a bad guy or two, inevitably by accident, while showing the perils and even the cruelties of old age. The pleasure in the book is that readers so identify with Oldguy that they will find themselves shaking their fists at those darn kids—even if they are those darn kids.

Trowbridge has turned the indignities of Oldguy’s oldness into his superpowers. In a poem called “Combat Moves,” we learn that Oldguy can, when in a tough spot, employ the “denture grapple,” the “taser cane,” and the “stupefying drone about the old days.” Indeed, Oldguy’s misperceptions and wanderings into memories (inevitably the wrong ones) end up being the one-two punches that foil his enemies. In “Oldguy: Superhero vs. Magneto,” Oldguy fails to even notice the evildoer to the point that,

When he

wanders between Magneto and the next victim,

Magneto thinks his enemies, the entire

human race, have resorted to mockery

as a weapon: sending out a diapered codger

to confront his near omnipotence.

The most interesting poems are those in which Oldguy faces his archnemesis, Death. Except that, like a geriatric Bill or Ted, Oldguy fails to cower in fear. Instead, as Death builds terrifying metaphors out of hot air, Oldguy focuses on the literal: Death has no meat on his bones, so Oldguy tries to loan him his L.L. Bean catalog for “some winter wear” to keep him warm. (Such a focus on the practicalities brings to mind the narrator of Jim Hall’s “Maybe Dats Your Pwoblem, Too,” another workaday superhero.) This has the effect of turning the tables and getting Death monologuing about his past like the tritest of Bond villains. Oldguy’s inadvertent victories recall the Pixar short “Geri’s Game,” in which an old man plays chess against himself and the prize is his own dentures.

The chief joy of this book lies in the details—as when Oldguy recollects a smog “thick as Aunt Sally’s goulash,” or, in his earlier days as Youngguy, he brings Artie Shaw’s band to his high school prom and “outshines Shaw with a tonette solo.” And in spite of Oldguy’s leaky bladder and creaky bones, this is a hopeful, affectionate book that will make even the young ‘uns want to learn what on earth a sarsaparilla is. Tim Mayer’s energetic, color-saturated artwork is a perfect fit for the poems, particularly in the Mike Judge-like background characters and the careful details of Oldguy’s super-suit.

Furusato, by Michael Cantor. Kelsay Books, 2019.

Light contributor Michael Cantor has put between covers a range of poems so broad and yet of such a single mind and voice that they do strange things to one another. By beginning with the most melancholy and delicate of the poems in a section called “Querencia,” Cantor establishes a mood that even the wry second of four sections, “A Portrait of Gorian Dreigh,” can’t entirely escape. The whole book feels crepuscular, and while we can tell jokes at twilight, the day is still dying no matter how hard we laugh. Cantor suggests this orchestration of moods is deliberate, especially when he tells the same story in two very different ways in different sections of the book. “Haibun: Divorce” uses a prose-verse hybrid form from Japan to tell the painful story of a couple’s quiet, brittle divorce. The same story is told in Carroll-like not-quite-nonsense words in “Wabberjocky”:

The in and out transformed to on and off,

her wabberjocky jockey went to sea

with shockleshells and writhyrambs, while she

frick-frocked with scrumptious scullions in the froth;

We know the story from the earlier poem, so the transformation to nursery neologisms is both funny and scalding.

Overall, the poems are incisive, the craft is intricate, and the stories are unique and poignant. Cantor’s speaker is a successful man with a life of sophisticated regrets and surprisingly homey triumphs. The title, Furusato, is a Japanese word meaning “hometown.” In the title poem, the speaker escorts a high-powered Japanese executive from the airport to the Manhattan office where they will do their negotiating. When the speaker tells Mr. Kondo that New York is his furusato, the visitor looks out the car window at the burned-out South Bronx and becomes suspicious of his companion. Cantor leaves us to speculate about how the negotiations proceed. This poem ties together the book’s themes: the truth leading to trouble, the unexpected stakes of specific situations, and the tension between heimisch, as the speaker’s pogrom-escapee ancestors might have said, and highfalutin.

For those who might have a hard time reconciling the first two sections, the third, “The Tummler,” shows the reader a place where dark humor and melancholy were besties: urban American Judaism in the mid-twentieth century. A tummler was a fixture of Borscht Belt entertainment venues whose job was a mishmash of emcee, cruise director, and standup comic. This is the shortest section of the book, but, like a tummler, it explains and coheres the rest. Cantor begins with a boy noticing a drunk on the El train, realizing it’s his father, and deciding whether to wake the old man at the stop near their home:

And if I do wake him, what do I say?

What would he say? We almost never talked,

Do I simply pretend this never happened,

go home and wait for him to show up later,

continue living in my separate world?

I tapped his shoulder. And then again. Again.

If you choose to begin with the funny second section, you will find lots to crack a smile at even as an uneasy twinge makes itself known. There is a Fib (a poem based syllabically on Fibonacci’s sequence) that can stand alongside A.E. Stallings’s “Four Fibs” in its innovations with the form, and a sonnet called “Gallery Opening” that could be used by women as a Rorschach test for their Tinder dates. Form afficionados will finally receive an answer to the question: A line of trochees—can you snort it?

Furusato is full of contrasting moods, glamorous East-West meanderings, and unusual forms (including Cantor’s own invention, a tanka-sestina hybrid). Its verbal precision and emotional honesty—and razor wit—make it a book worth the whiplash.

Bachelor’s Buttons, by David Southward. Kelsay Books, 2020.

When I received this book, the author had thoughtfully included a Post-it with the page numbers of the poems he considers to be light verse. I only sort of regret to inform him that there is a lot more in here to appeal to Light readers than he thinks. This quiet and thoughtful collection is largely quite serious, as in a poem about the multiple meanings of a lover’s homemade bread, and in the virtuosic “Synchronized Diving,” which echoes in its form the sport it describes. But in other poems, Southward has a habit of matching heavy subjects with light forms—turning what might be dense, contemplative, eat-your-vegetables-they’re-good-for-you verse into rollicking and enjoyable conversations about big ideas.

Some poems in this book imagine possibilities you probably hadn’t considered, as in a meditation on men’s nipples, and a lengthy speculation on what Whitman would make of our present sex-saturated culture. The short iambic lines of “Walt Whitman, Are You Watching?” breathlessly tour the museum of twenty-first century depravities, pausing to ask,

Can poetry make any sense,

O Captain, of our prurience?

Shall masters of the cell-phone arts

(who publicize their private parts

to strangers querying “how hung?”)

presume the body electric sung?

In a similar vein, “Bosch Triptych” considers the painter’s “Garden of Earthly Delights” and the lure of its sensuality even when it descends into chaos. The poem employs long, descriptive lists of items in the painting, but Southward’s most interesting choice is the galloping triple meter that undercuts any Christian recrimination. “Garden of Earthly Delights” ends carnally, without having achieved heaven but also without the grotesqueries of Bosch’s hell. In effect, Southward shows us the pleasures of physical rhythm by employing aural ones. The poem is safe to consume in public.

Light-verse lovers will feel the thrill of discovery in a poem, “Ex-Olympian,” that challenges itself to find several rhymes for “Oscar Pistorius.” (My favorite: “uxorious.”) “Bi-Poetic” invents a new form, “hermaphroditics,” for those times when “the muscles of a formalist” and “the more supple / curves of free verse” seem equally attractive. “Lessons of Etymology” tackles the sources of eponyms thematically, pairing Amelia Bloomer and Jules Léotard and, as it were, putting a Sandwich in Lord Cardigan’s pocket.

Bachelor’s Buttons probably won’t make you snort your coffee or startle the cat with laughter, but it will stir your imagination and demand continuing attention as you discover new aspects of its interplay of form and content.

Get the Hell to Work: Humorous Verse about Work and Life, by Thomas O. Davenport. Kelsay Books, 2020.

Haven’t been to your office since March? Getting a little nostalgic for the smell of the commuter train or the burnt coffee in the break room? Thomas Davenport has got you covered.

In poems that range from airy villanelles to sonnets that weaponize couplets as punchlines, Davenport addresses nearly every cubicle-jockey bugbear and foible. This is true light verse, and the fun is not only in his observations but in the way he presents them. Anyone who rhymes “narcissist” with “deep-fried horse’s arcissist” is someone you want sitting next to you in coach when your business flight is stuck on the tarmac. Davenport also has the rare skill of writing long lines of seven or eight beats that don’t sag in the middle like a bad desk chair.

In our present historical moment, many of us who labor at corporate jobs miss the real human contact we have with people who also use “circle back” and “won’t have the bandwidth until next week” unironically. If you know such a person, send them this book. Then have a Zoom meeting to discuss it.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets Abridged Beyond the Point of Usefulness, by Zach Weinersmith.

As with David Southward’s book, I must begin a positive review by telling the author he is wrong. These abridgements, into tetrameter couplets, are not at all unuseful, and in fact, they serve three laudatory purposes: first, they make clear the story (or potential multiple stories) in Shakespeare’s originals by condensing them to essentially, “So there’s this Hot Guy, see…”; second, they pretty much force the reader to reread the original sonnets, which is always a worthwhile exercise; and third, by using contemporary idiom, they illuminate the universality of Shakespeare’s themes, minimizing fear of the language in order to find out what happens next. The scholarly among you may shriek at “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” being reduced to,

Summer’s bad, then dies. You won’t.

(Okay, you will, but poems don’t.)

but Weinersmith’s version just might get a resistant sixteen-year-old to find out exactly what Will did say that resulted in that summary.

Weinersmith is the creator of several multimedia projects, most prominently Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, a web comic that is often philosophical and (to quote the author) “geeky.” His sonnet abridgements (perhaps better thought of as sonnet concentrate: “Just add Elizabethan activator and mix thoroughly”) clearly show the influence of a multifaceted online existence paired with real scholarship. The resulting tone is of complete irreverence except where reverence is truly earned. In his introductory essay (the front and back matter are considerably longer than the 154 couplets), Weinersmith carefully outlines the directions various editions have taken since the Thorpe in 1609, and he clarifies the relationships among the poet, the Fair Youth (“Hot Guy”), and the Dark Lady without oversimplifying. Indeed, sonnets 40-42 are referred to as “the ‘Hot Guy did my girlfriend’” sequence. Not exactly Harold Bloom, but not inaccurate either.

Among Weinersmith’s gems is “How like a winter hath my absence been,” which distills down as follows:

Summer’s flowers, autumn’s fruitage:

It’s all just winter sans your cute-age.

And in a sort of anti-anti-blazon, he turns “My mistress’s eyes” into,

My girl has little sex appeal.

But has this virtue: she is real.

The crowning achievements of this little ebook are the original poems at the end—one called “A Poem Summarizing the Above, as Narrative,” and another, “A Poem About the Sonnets Through Time.” I will never again teach the original sonnets without Weinersmith’s literary history in verse. I mean,

Later critics, often prudes,

Saw “courtly love,” not sex with dudes.

“There’s nothing gay or even churlish

In lusting for a boy who’s girlish!

And even though a few are shady

A full 1/6th were to a lady!”

Somewhere, Marlowe is chuckling.

Also Over the Transom:

The Funny Thing About A Poem, by Randy Cadenhead. 2019.

Rhymal Therapy: Tasteful Limericks for Discerning Readers, by Phil Huffy. 2020.

The Powow River Poets Anthology II, edited by Paulette Demers Turco. Able Muse Press, 2021. How many times do you get a sequel in poetry? The Powow River Poets, a group centered in and around Newburyport, MA, published their first anthology in 2006, and now they are out with a second volume containing work by many poets familiar to Light readers, including Meredith Bergmann, Michael Cantor, Barbara Lydecker Crane, Robert W. Crawford, Rhina P. Espaillat, Midge Goldberg, A.M. Juster, Jean L. Kreiling, Alfred Nicol, and Kyle Potvin. Look for a review—of the light ones, anyway—in the Winter/Spring 2021 issue of Light.