If you have a book you’d like considered for a review in Light—one that includes a large helping of comic verse and was published within the previous 12 months, or will be published in the next eight—please send a copy to:

Barbara Egel

PO Box 408250

Chicago, IL 60640-0005

(Pre-print-run electronic copies may be sent to lightpoetryreviews@gmail.com)

Light on Their Feet

Reviews of books by Jane Blanchard, John Ormsby, and Marilyn L. Taylor

by Barbara Egel

Outside the Frame: New and Selected Poems, by Marilyn L. Taylor. Kelsay Books, 2021.

Don’t let the title, your previous knowledge of the poet, or the soothing, aquatic colors of the book cover fool you. After reading Marilyn L. Taylor’s new volume, you are likely to set this book down as though it’s dangerous. It’s as though you were lulled into boarding what you thought would be an innocuous amusement park ride, then were plunged into darkness, and then, a moment later, tossed back into the sunshine, unsure whether the next moment held pleasure or another plunge. Wikipedia tells us that this poet has passed eighty, and while the subjects of many of the poems point to age and to endings, the approaches and techniques are anything but stale or predictable.

If you look back over Light’s reviews in the last several years, you’ll read that collections which include both light and serious verse often partition the two from each other in separate sections. This is a fine path to take when themes or forms suggest an organizing principle. In her new collection, Taylor instead sets the light and the dark next to each other in an almost Petrarchan impulse of arrangement, planning the chemical reaction that happens at the turn of the page, setting the potassium and sodium next to each other and waiting for the reader’s casual splash of water to explode the whole thing. “No Two Exactly Alike” explores the poet’s habit of declining a walk in the snowy woods in favor of staying in and writing about a walk in the snowy woods. It’s a gently chastising poem from the perspective of someone who loves and is exasperated by the poet. On the facing page is “Snow Mist,” which rhymes “sodden trees” with “moldy cheese” and completely disrupts the moody silence of its page-mate.

There’s an even more shattering example of such juxtaposition toward the end of the book. Two poems about burial and decay are printed on facing pages. “What Becomes of Us” is a terza rima tour de force. First of all, what better form for lines like “ . . . Now we interweave, / we press together in these tangled spaces / dank with mold and liquefaction . . .” than one that braids its rhymes together? The poem itself explores the sensuality of rot, the life cycle of a composting corpse generating new green shoots, “practicing the dank rituals of botany,” and ends with an ontological outcry that in less capable hands would fall flat but here pierces the silence of the tomb.

(Yes, you’re still reading Light, just give me one more minute.) The facing page holds “Posthumous Instructions,” a sonnet from her 2004 collection that features some very dark humor. The speaker of the poem has been cremated and is getting used to her new state. The first stanza rhymes “urn” with “learn,” and “go home” with the fantastically slant “clinkerdom.” In fact, it’s the rhymes that give us permission to snicker, even as we’re a little uncomfortable with the contents. Taylor’s message for the book is especially clear here: the end of life raises enormous questions that demand to be taken seriously, but you will get the answers only if you bring your sense of humor. While ”Posthumous Instructions” has been around a while, its pairing with the darker poem gives it new shades of meaning and impact.

Taylor’s technical skill has always been irreproachable, but this book is a level up from what she’s done before. With “What Becomes of Us” and so many others, she delivers a master class in the marriage of form and content, from the selection of received form to individual sonic choices. “Iron Man” is a sonnet about a beloved’s last days or hours in a hospital bed. The speaker in the poem tunes in to the patient’s breaths, the duet of heart and lungs continuing in spite of the effort it takes. Sonically, the poem incorporates a density of sound—perfect end rhymes, internal rhymes, and rich repetitions of other sorts—as though by backstitching what we hear, it can prevent the moment when the breaths stop. Here’s what I mean:

. . . your heart fixated on creating

a steady backbeat for the crusty rasp

of respiration. I saw how your hands

had interlaced themselves into the grasp

of one another—like the sweet demands

the dying lay on those already grieving.

Because the forward motion of the lines always casts us back with matching sound, there’s no room for that dreaded silence. Even the volta is elided so as not to jar or interrupt the steady respiration.

A crown of sonnets called “Notes from The Good-Girl Chronicles, 1963” uses the linked poems to present a snapshot of a moment in history when women felt they were on the verge of something—exhilarating or terrifying, depending on the woman. Here again Taylor uses rhymes that light-verse readers will love, but brandishes them like a candy-coated scalpel. For example, “rack of lamb” and “ad nauseam” come together in the monologue from the executive’s wife who goes through the motions but fears the future.

There are also free-verse poems that showcase that ineffable difference between free verse written by someone who has meter in their bones and someone who does not. “After the Midnight Phone Call” is a spare, uncapitalized column down the side of the page, which is exactly as much as it should be. Rhyme or assertive meter would tire it out, but it takes a poet who has mastered form to understand this so fully. Just to increase the level of difficulty, many of the free-verse poems are light (or “light” as it’s defined by this book). “The Day After I Die” anticipates all the wonderful things—from a unified theory of physics to a Billy Collins intervention—that will happen in the world as soon as the speaker is no longer there to benefit. The descriptions of these absurd happenings are sufficient without further sonic fireworks.

I will release you from the seriousness and shop talk since I hope by now I’ve convinced you of the value and impact of this book. Let’s move on to the fact that Marilyn L. Taylor is funny as hell. Four of these poems have appeared in Light, and a lot more would be welcome in its pages. Others are familiar from previous Taylor collections, but they’ve found their home here quite comfortably. Who else would write so operatically about breast self-exams? The rhymes in “Another Thing I Ought to Be Doing” come from way far out in left field and yet don’t feel like a reach in terms of the sense of the poem. For example, the speaker inquires about her breasts,

“… where

were they when I was fourteen, fifteen,

and topographically a putting green?”

Reaching for a metaphor for flatness and coming up with the dad-joke “putting green” is so much more mortifying to a teenager than any other “-een” I can think of. And sliding “topographically” into the pentameter with such ease is just showing off.

Her parodies are wonderful. “Tackiest of Trees” appeared in Light and sits happily in this book. Another, “Late Spring, Early Fall” (also in Light) would give poor Gerard the vapors, starting, as it does, with “Margaret, are you gagging / since your body started sagging?” But even some of the parodies call back to the book’s theme. “Lonely as a Cloud” does not waste time on a “vacant and pensive mood.” Here you go:

So here they come,

one month to the day

after your funeral—

the goddamn daffodils

you planted last fall.

Marilyn L. Taylor is angry and celebratory and elegiac and hilarious and so skilled it’s breathtaking. If you think you know her work, the comfort of familiarity will be smashed by something new, exciting, and brave. If you think a poet over forty, or seventy, for that matter, has nothing left to say, let her prove you very wrong.

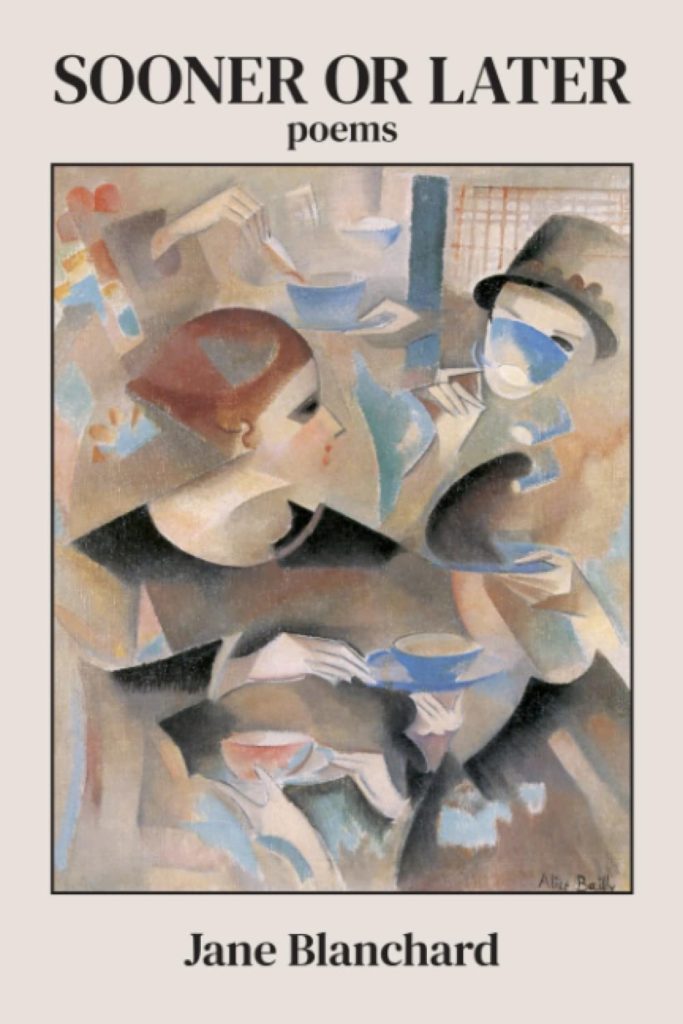

Sooner or Later, by Jane Blanchard. Kelsay Books, 2022.

Light contributor Blanchard has a unique voice, one I encourage you to spend time with. Her book of mostly light poems makes one feel sophisticated to have completely gotten the jokes and the worldliness behind them. Rather than laughing aloud, you’ll outwardly show a wry half-smile while inwardly, you’re throwing yourself a little party for your own cleverness. These are poems for people who have been through some stuff and emerged with their sense of humor intact. In contrast to Taylor’s book, which runs the spectrum from tragic to hilarious, Blanchard keeps the mood in a narrower range, and the effect is prismatic: depending on the light your own mood shines through the poems, they can be funny or wryly serious.

A number of the poems with this quality could be collected into a chapbook called The Mature Woman’s Guide to Love and Romance. Blanchard is a realist when it comes to love later in life, as demonstrated by poems like “Accommodation,” in which she suggests that nature somehow balances things out when complementary parts start to slide.

Of any beauty I once had

There is too little left;

Despite this unattractive fact,

I do not feel bereft.

My doting spouse seems not to mind

I have grown plainly old;

His eyes have gotten weaker since

He first did me behold.

On a good day, I’d find this congruence of decrepitudes pretty hilarious. On a bad day, the poem and the mirror both would reflect me, but with a steady undertone of mockery for taking myself so seriously.

Her relationship poems, especially the ones about long-ago-ended pairings, are both rueful and revelatory. Blanchard’s pragmatic musings make for a wry how-to guide. “Strategy” instructs the following:

Encountering an ex again,

Avoid all talk of there and then.

Speak only of the here and now;

If ex should balk, show him/her how.

Be sure to shun the question “why?”

(Its answer often is a lie.)

Maintain some semblance of composure;

Abandon any hope of closure.

Apart from such tutorials on the ins and outs of romance past and present, there’s so much more good light verse in here, and the humor manages an unusual restraint. There are political poems on topics ranging from the grammar of Justice Scalia’s death to carpetbagging lobsters causing international incidents. In her light verse, Blanchard’s meters demonstrate the sort of perfection that causes one to imagine the poems walking around with books on their heads to discipline their forms, but this potential stiffness is beautifully balanced by her rhymes. She’s particularly masterful at doing what is generally frowned on in serious formal verse: rhyming on an insignificant word for comic effect. In “Artificial Intelligence,” a rant in sonnet form about updating software, Blanchard’s end-rhyming words like “my,” “then,” and “to” keep the poem galumphing along at just the pace of frustration you’re meant to experience while the rhymes themselves prevent the reader from flying off the rails completely. In “The Brouhaha Re: Panama,” rhyme does heroic work in delivering the humor. My particular favorite is “wealthy codger” / “cagey dodger.”

Some lovely poems dip toward the serious side. “Natural Disaster” is a heartbreaking match of form and content in which shortening the last line from tetrameter to dimeter catches readers’ breath in their throats.

The complex unity of the voice in this book means you will want to reread both the lighter and the more serious poems, allowing each new encounter to show you more. But lest you think that Blanchard is all arched eyebrows and world-weariness, one tiny poem emerges among my favorites. It starts with an abandoned Goldfish cracker on a church floor on Christmas Day, and ends with a recognition of all the miracles, mundane and otherwise, the season holds. If you search for a new timbre of light verse, Sooner or Later is far more than faute de mieux, and Blanchard’s poem “Faute de Mieux” is only part of the proof:

Perfection is impossible to find:

We think, “Oh, yes!” then “No!” then “Never mind.”

Sometimes we settle for the good enough:

To live with disappointment can be tough.

At other times we go with the less bad:

We later learn, again, we have been had.

Avoid disappointment. Read this book.

It Started When You Farted: Witty Rhymes for Playful Minds, by John Ormsby, illustrated by Andrea Benko. Maple Syrup Publishing, 2021.

After seeing the title, and especially after enjoying and writing about Jane Blanchard’s subtleties, I did not have high hopes for this book. I don’t mean the fart aspect, though flatulence is best examined sparingly. No, it was the subtitle that made me sigh a deep sigh of the show-me-don’t-tell-me variety. Then I opened the book and started reading. John Ormsby’s work is wickedly clever, technically skillful, and lots of fun.

Let’s start with the humor. Initially, it was challenging to gauge the intended audience for this book. The illustrations, which are bright, clear, and colorful, might suggest it’s aimed at children. However, the tone and the topics of many of the poems suggest those children are likely restricted to the milieux of Addams, Baudelaire (as in Violet, not Charles), or Gashlycrumb. “Creepy Crawler” illustrates what I mean:

A friend of mine who used to teach

Said some kids he just couldn’t reach

A situation made more grim

For they were learning how to swim

The accompanying illustration would suffice for Stevie Smith’s “Not Waving But Drowning,” which is usually not thought of as a thigh-slapper.

Whatever Ormsby’s intent, we’re lucky he didn’t aim his work at kids because some of the best poems are about very adult subjects but come wrapped in rollicking meter and particularly deft rhyme. “Alpha Mail” lets us in on just what the postman is thinking about us, and it’s not pretty. “Tudor Suitor” runs through all of Henry’s wives in search of a male heir, ending with Elizabeth I, who “showed the world it takes a girl / To do it like a boy.” “Secret Santa” is a long poem about the office gift exchange and the various personality defects, petty revenges, and perils of the punchbowl that are particular to workplace Christmas parties. What makes this so much fun is the good-natured cynicism captured in the rhymes. The fact that some of the rhymes feel like a reach but land anyway only makes them more effective. For example, when a would-be lothario is emboldened by the reception of his gift, we get “That perfume seemed to animate her / I’ll say ‘hi’ by the laminator,” which is cause for both groaning and secretly high-fiving Ormsby at the same time. “Creature Feature,” a poem about how dining etiquette goes all to hell in movie theaters, is particularly rich with unexpected rhyme. If you want to know what rhymes with Fred Astaire, pommes parisienne, bourgeois, Oreo, and crotch, you’ll just have to get the book.

While the longer pieces give Ormsby room to play, the short ones, quatrains mostly, are surprising for how much they can pack in. “Ready To Chuck It All In” is about the Queen of England’s ninety-fourth birthday, effusively celebrated by everyone—or almost. The title hits you later. “Mane Attraction” encompasses everything Ormsby does well: punny title, clever rhyme, and a spin on the situation that I’ve not seen before. Here it is:

Rapunzel’s prince betrothed his love

Her freedom he was wishing her

Alas, he could not climb above!

(She’d used too much conditioner)

It Started When You Farted is a whole surprising package. While the poems don’t need the illustrations to be effective, the pictures are a lot of fun, and Ms. Benko often adds touches that are amusing all on their own. For example, a couplet about whole grain bread is accompanied by a picture of a bakery called “You Deserve Butter,” and Benko solves the riddle of what Elton John would look like as a bee. If the actual contents aren’t enough to spur you to purchase, all proceeds benefit the UK Teenage Cancer Trust. What poetic accolade also rhymes with “mensch”?

One note for Mr. Ormsby’s next book (and there ought to be a next book) is that he needs an editor who understands light verse. In a few places, line breaks don’t make a lot of sense, and in spite of the UK’s current budgetary woes, I’m pretty sure there hasn’t been a punctuation shortage yet, though you couldn’t tell from this book. Those small quibbles aside, John Ormsby’s is a welcome voice in the light verse chorus, and I hope to hear more of his harmonious cacophony.

Also Over the Transom

Real Rhyming Poems, by J. M. Allen. Kelsay Books, 2022.

Turns and Twists, by James B. Nicola. Cyberwit.net, 2022.