If you have a book you’d like considered for a review in Light—one that includes a large helping of light verse and was published within the previous 12 months, or will be published in the next six—please send a copy to:

Barbara Egel

PO Box 408250

Chicago, IL 60640-0005

(Pre-print-run electronic copies may be sent to lightpoetryreviews@gmail.com)

Light on Their Feet

(Reviews of books written or edited by Bruce Bennett, Edmund Conti, Robin Helweg-Larsen, Steven G. Kellman, and A.E. Stallings)

by Barbara Egel

Just So You Know, by Edmund Conti. Kelsay Books, 2018.

This is Edmund Conti’s first full-length book of poems, which really represents criminal negligence of a literary sort. It should be his fifth book. Or his forty-fifth. It had just better not be his only because we need a lot more of what’s in here. To take a Conti-ish approach to this review—which is to say, to tighten a theme inside, outside, and around a subject so intricately that its shoelaces are macraméd to its intestines and it still all makes sense—we should talk about light. Of course, Conti is a master of light verse who has long enlivened the pages of Light (from the time it actually had pages). He is also, metaphorically, a magician of light—the rays that can warm and brighten, scorch and scar. A lot of light verse is a single beam that can be comprehended in one go, but Conti plays with prisms, which complicate interpretation: it’s foolish to assume that you’ve appreciated all the refractive surfaces of a Conti poem even upon multiple readings. What does this mean? I’ll do my best to explain.

The voice in most of these poems is that of a friend you would want next to you while you’re waiting for probably-negative test results at the hospital. That is, it’s wry, laconic, honest, and incisive, and never flubs a punchline. The title poem, which is also the first poem in the book, introduces the reader to this voice by stating an irrefutable, crucial fact: “I am not Billy Collins.” The poem goes on to be not-Billy-Collins by cataloging a list of very Billy Collinsesque images, all the while emphasizing the differences between the poet and the Poet Laureate:

And me? Well, that’s it.

If I have an ancient mourning vase from the Xin

Dynasty (and I do) it stays on the mantel

and not next to an album of Bix Beiderbecke

casually left out beside the half-finished

bowl of cornflakes and Belgium strawberries.

This voice also knows just when to stop talking, and never (as perhaps with a certain poet whose name rhymes with Zilly Dollins) falls in love with its own cleverness. A fine illustration of this can be found in the shortest poem in the book, which reads like a Zen koan written by Mark Twain:

People Like Us

Some are.

Some don’t.

Indeed, sometimes Conti’s terseness might leave you feeling as though you didn’t entirely follow but somehow ended up in the right place anyway, as in “Death Warmed Over”:

That’s what my son said when I said

I wanted to be cremated. And, of course,

the other son, sibling that he is, asks

before or after you die? My wife

declines comment. She has already told me

she doesn’t want any cameo appearances in

any of my poems. Unless it’s a rhyming will.

No, she didn’t say that. She could be very funny

if she would let me.

If you’re noticing that in two of the poems above, Conti has Marianne-Moored the title into the body of the poem, you’re on to something that’s crucial to catching light from all of his facets: Conti will wrap a theme or a trope around whatever part of a poem he can in order to infuse it into every syllable and line break. This includes the title; allusions to literature, history, the writing life, or household appliances; and the effect of the poem after it’s read. Such efforts are nicely summed up in the third stanza of “The Top Ten Reasons You’re Going to Like this Poem”—the third stanza starting, naturally, with “8”:

8. It has accessible irony in claiming not to mention Death Panels while cleverly mentioning them.

It’s not the Death Panels apophasis that gets me, it’s the term “accessible irony” that doesn’t really land—and pass its judgment—until the third or so reading.

Thus far, my examples have fallen firmly in the category of light free verse, but there’s real versifying virtuosity here, too. A cento made of the first lines of Shakespeare sonnets enjambs lines that heretofore appeared a hundred or so poems apart, and “Un Bel Di” is an original sonnet filled with entomological heartbreak. In another Contian irony, a poem that both parodies Hopkins’s “Pied Beauty” and talks about poetic dabblers is ridiculously skillful, rhyming “gem” and “apothegm.” But as noted, Conti is agile—and funny—with or without rhyme and meter. At times, one imagines that he employs free verse for its run-on qualities, as in one of the book’s funniest poems, “Godsend,” which imagines an e-mail from God punctuated with kicks in the stomach as the deity reads the poet’s less-than-enthusiastic mind.

The Olympic-level test of a light verse poet is whether they can write a serious poem that doesn’t dissolve in either irony or pathos, and Conti manages this in a few poems in the book. “Saint Frosty” is about a snowman, for heaven’s sake, and includes real-life references to the anatomical repurposing of the carrot nose carried out by neighborhood kids. But it also (in a move reminiscent of Stevie Smith) points out the paradox of wanting to get warm while knowing that would be a very bad outcome. “Two-Zone Heating” contemplates the randomness of 9/11 and the ambivalence of those of us who suffered no personal losses on that day. That poem appears near the end of the book, and by then, we know this voice so thoroughly that the poem’s straightforward approach lends extra poignance.

As promised, I tried my feeble best to explain why this is an important book, but reading your own copy will be a much more satisfying way of understanding. And if enough of you buy it, maybe there will be a second one.

American Suite, by Steven G. Kellman. Finishing Line Press, 2018

Since poets are highly unlikely to get rich in actual money, we might consider “sales” of poetry in terms of how many times eyeballs sweep across a page. In that case, Steven G. Kellman has quite a marketing gimmick.

American Suite, a book of literary bios in verse, begins with Benjamin Franklin, proceeds in roughly chronological order, and delineates the end of American authorial history with Philip Roth. Along the way, Kellman includes the no-longer-fashionable (Richard Henry Dana) and the relatively forgotten (Charles Brockden Brown) in short poems enticing enough that after a first reading, one runs to Wikipedia and then revisits the poem, equipped with sufficient erudition.

This is a book that, frankly, could have been half as long. Not in terms of pages, but in terms of physical length from top to bottom, since none of its poems passes the half-page mark. This also brings the reader back to favorite pages since the poems—witty, memorable, and rhyming—are perfect mnemonics for remembering who’s who. If you have to think hard about which Crane is Hart and which Stephen, the poems about each will quickly cure you of that confusion. Kellman also uses this very short form to concentrate wildly divergent facts about a subject into a tight few words. This tactic is exemplified in the poem about Marianne Moore, which includes her penchant for spiny animals, her love of baseball, and the fact that she was once asked by the Ford Motor Company to name a car:

Marianne Moore adored

Pangolins, hornbills, porcupines—

Horned creatures hard to handle.

She also worshipped Mickey Mantle.

Asked by Ford to name a car,

She was not meek.

She offered: Mongoose Civique.

Rejecting with thanks a sure hard sell,

They went instead for Edsel.

I rather hope that the trochee at the end is an admonition to Ford about the poetic opportunity it missed.

Similarly, the value of lesser-known but significant writers such as Tillie Olsen comes across so clearly in the poems about them that one ignorant of their work wants to read them in order to understand exactly what Kellman so appreciates. The brevity and concentration of these poems works like a potent amuse bouche: get a taste and then seek out the entire cuisine.

Particular favorites among the affectionate poems include those on Willa Cather, Frank O’Hara, and Flannery O’Connor, but Kellman is not universally laudatory. Personages such as H. L. Mencken (the verse about him starts with the wonderful line, “A connoisseur of kvetch”) are examined warts and all. The brilliance along with the antisemitism and madness of Ezra Pound is jammed into four evocative lines.

American Suite is quite funny even as it leaves room for pathos. When Kellman gets to the Modernists—Stein, cummings, Stevens—both their style and their moment in history are targets. For example:

him

within the circles cummings traveled

pious thoughts came all unraveled

while others raved at capitalist tools

he saved his rage for majuscules

Kellman has a few other approaches to the funny ones. In a true parody, he updates “The Road Not Taken” to account for contemporary sylvan husbandry (especially in New England, where they take such things very seriously). At other times, a poem ostensibly about one figure strongly alludes to another. Take “Papa H’s Waltz,” a parody of Theodore Roethke’s poem that not only riffs on Hemingway’s nickname, but serves as a funhouse mirror on Hemingway’s life. Or consider the weirdest of these concatenations, in which Jay Gatsby prefigures Otis Redding “on the dock of the bay.” (A little Googling taught me that Kellman is not the only one to make this connection—mostly based on mood—between the novel and the song.)

Not every poem is an unblemished success. The one on the Plath-Hughes household reaches for a metaphor through rhyme that—even though it doesn’t quite work for me—still results in a shattering picture of that sad milieu. And perhaps I’m missing vital information, but except for the pun on “beets,” I’m not aware of how Ginsberg is so specifically associated with borscht that it makes for a homerun punchline. All that said, however, American Suite is a lot of fun. The poems you understand upon first reading will make you feel clever, and the rest will make you feel edified. And you will go back to them when you read or teach the authors in question. (Literature profs, buy this book!)

Like, by A. E. Stallings. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018

This review will be a bit more impressionistic than usual since loftier critics have lauded Like with tremendous sophistication in The New York Review of Books and Los Angeles Review of Books, among others. The book presents as deceptively tidy. If you know Stallings’s work from Light or other venues, you expect this: formal virtuosity and an almost physically impossible resonance of theme and music from so few marks on a page. No metrical substitutions or near rhymes that can’t be justified and ultimately cherished upon examination. In Like, it feels as though she acknowledges these expectations and is messing with us. First of all, the book is arranged alphabetically by title, which might feel like surrender on the part of the poet—avoiding questions of position and association. But unsurprisingly, the alphabet is on her side, and the flow from beginning to end gets caught in little eddies of theme. One example focuses us for a moment on contemporary motherhood, beginning with “For Atalanta” and ending, itchily, a few pages later with “Lice.” Indeed, a particular achievement of this book is that it can talk about motherhood without reverence or schmaltz while also not downplaying how hard it is to do it right, especially in the small moments. “Lost and Found” applies an epic conceit to the search for missing Legos and socks that calls to mind Eavan Boland’s “The Journey” in its insistence on the importance of mothering’s less noble but nonetheless crucial tasks.

In general, Like is not a light book. It is relentlessly contemporary, and our present moment is not a happy one in most places on the globe. When a poem approaches humor, it’s with a kind of wry weariness that marshals intelligence to cheer us all up, as when Hesiod and hair dye occupy a wintry afternoon at the salon. A great poet worries about her graying roots. If that doesn’t comfort you, we have nothing more to discuss.

What does qualify for inclusion in Light is the voice here. It has a sense of humor even when the theme of a poem is somber or the end is dark. “Psalm Beginning with Two Lines of Smart’s Jubilate Agno” muses on mourning rituals after the death of cats, in a rushing cadence that sweeps Moses and eyebrow pencil in its path. “Shoulda, Woulda, Coulda” conjugates disappointment in a way especially affecting for grammar nerds. The title poem, a sestina that uses “like” at the end of almost every line, examines that word from every possible angle: how it signals approval on social media without really meaning anything, how it colonizes millennial speech like an invasive species, how it turns reality to simile to facsimile.

The kind of mind that is turned on by wordplay, by unexpected intertextuality, and by punchlines that leave bruises—in other words, by the best light verse—will love this book. It might not make you guffaw, but it’s a good companion for traveling into whatever our collective future may hold.

A Man Rode Into Town, by Bruce Bennett. Foothills Publishing, 2018.

The prolific Bruce Bennett has a new chapbook. Or a verse-short-story chapbook? Or a Western-verse-short-story chapbook? Whatever it is, it is very clever. Imagine watching High Noon or [fill in favorite Western here] in slow motion and having the peripheral or interior aspects of the movie—the stuff that doesn’t make it onto the poster—converted into canny observations in verse. The focus is not only on the taciturn, no-nonsense cowboy at the center of the tale but on his horse, his gun, his spurs, random bystanders, and of course, his love interest. In Bennett’s capable hands, the Old West is revived in a variety of verse forms, each befitting its subject. If, in this historical hiccup of provocative Gillette ads, tabloid politics, and deep winter weather, you find yourself longing for something both familiar and stimulating, saddle up with this stranger.

Potcake Chapbooks, edited by Robin Helweg-Larson. Sampson Low Ltd.

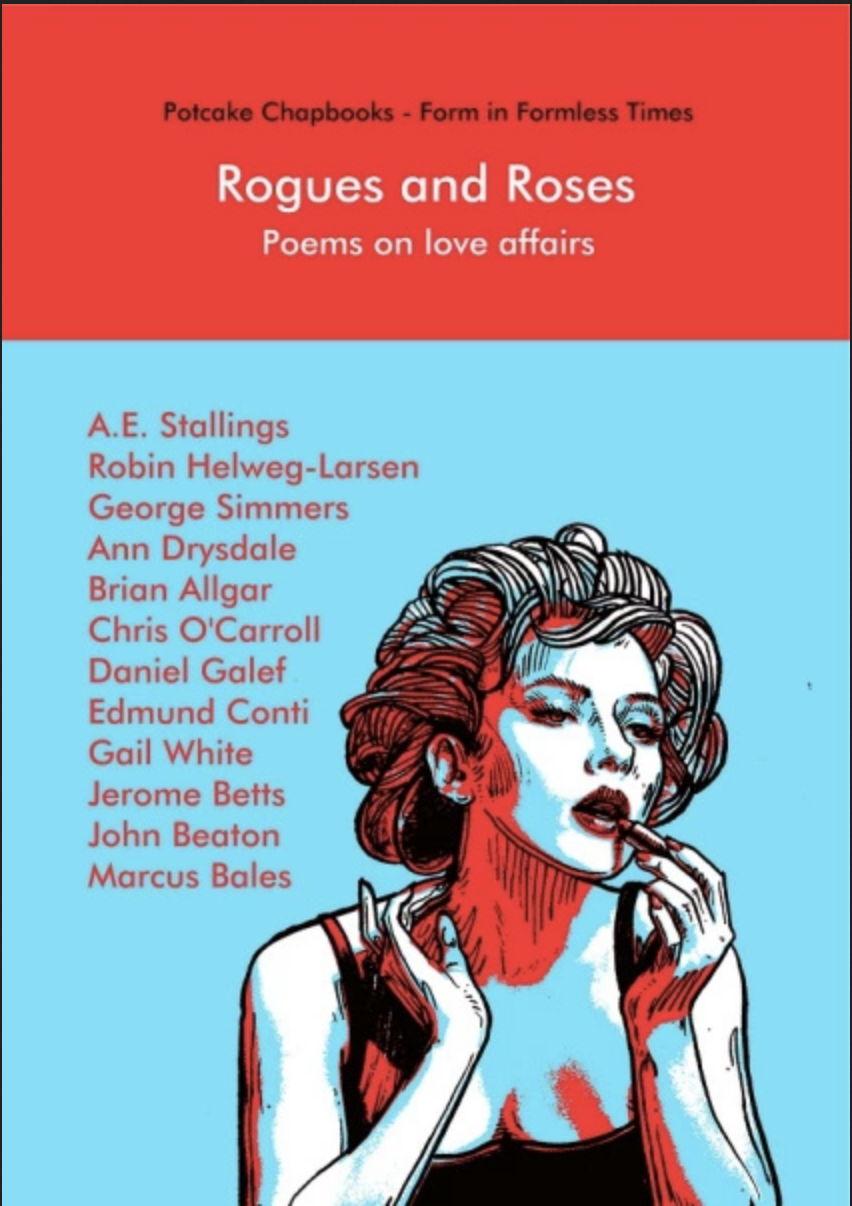

A new source for pocket-sized light-verse collections just rode into town as well. The Potcake Chapbook series is a collection (three, so far) of pocket-sized anthologies smaller than many cell phones. These books appear to be made specifically for Light readers in that the series “subscribe[s] to the use of form, no matter how formless the times in which we live,” the poems are selected to achieve that lovely balance between wit and sweetness—and sometimes outright belly laughing—that is the hallmark of so much good light verse, and the poets in the first two volumes are nearly all road tested and approved by Light‘s editors. Rogues and Roses covers love and sex in a surprising number of variations for thirteen short pages, and Tourists and Cannibals ranges from local holiday spots (Terese Coe) to escaping the heat others come specifically to find (A. E. Stallings) to learning languages (Robin Helweg-Larsen) to a hat-tip to one’s homebound god when in a temple on the other side of the world (Gail White). Careers and Other Catastrophes just came out. I haven’t seen it yet, but if it matches its sisters, it’s worth getting the whole trio.

The Potcake books include lovely little three-color illustrations, and for less than the cost of a latte (plus postage from England) you can amuse yourself or give a truly unexpected gift. Either way, the mix of poems and the quality of the work will delight and surprise. This series should continue and thrive.

More Goodies Over the Transom

Out of Nothing: Poems of Art and Artists, by James B. Nicola. Shanti Arts Publishing, 2018.Odd Socks, by John Robert Brown. Iron Press, 2018